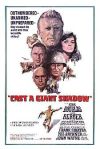

Cast a Giant Shadow (1966) is a fictionalized account of the story of David “Mickey” Marcus, a Jewish colonel in the U.S. Army who fought in the Israeli War of Independence. Before his involvement with the nascent State of Israel, he served in WWII in Europe, and was part of the occupation government in Berlin after the war. Among other duties, he was involved in the liberation of the Nazi concentration camps. Marcus grew up in Brooklyn, received a nominal Jewish education, and attended West Point.

Cast a Giant Shadow (1966) is a fictionalized account of the story of David “Mickey” Marcus, a Jewish colonel in the U.S. Army who fought in the Israeli War of Independence. Before his involvement with the nascent State of Israel, he served in WWII in Europe, and was part of the occupation government in Berlin after the war. Among other duties, he was involved in the liberation of the Nazi concentration camps. Marcus grew up in Brooklyn, received a nominal Jewish education, and attended West Point.

David Ben Gurion named him aluf [general] of the Israeli Defense Forces, the first person to hold that title since Biblical times. Marcus’s advice and participation was critical to Israeli success in the war, and he is remembered with great fondness in Israel. He is also the only soldier buried at West Point who died fighting under a foreign flag.

Marcus is played by Kirk Douglas, and his son, Michael Douglas, had his first film role as a jeep driver. Yul Brynner (who looks eerily like Moshe Dayan), Topol, Angie Dickenson, and Frank Sinatra also appear in the film. John Wayne plays an unnamed American general.

Commentary

Col. Mickey Marcus was one of the “Machal” fighters (the Hebrew acronym for Mitnadvei Chutz La’aretz, “volunteers from outside Israel”). This film tells his story, and along with it, gives one of the best screen depictions of some of the most famous aspects of the Israeli War of Independence.

Aside from a schlocky romance with a beautiful Israeli that Hollywood could not resist adding, the screenplay is largely in keeping with the only English-language biography of Marcus, Cast a Giant Shadow by Ted Berkman. The rest of the story is fairly reliable, and the film was shot on location in many of the places where battles in the War of Independence were fought. I recognized Latrun, and a particularly bad spot on the road to Jerusalem, as well as the famous “Burma Road.” (These are all places you can visit in Israel today.)

Many of the details are accurate. There were indeed busloads of refugees, many of them survivors of the death camps in Europe, who were handed guns at Latrun and sent in to fight. Women served in combat and were among the truckdrivers who made up the convoys that traveled under fire carrying food and water to the Jews of Jerusalem. The Israelis were so short on munitions that they resorted to many ruses to make the Arab armies believe they had more firepower than they really did. The “Burma Road” really was that perilous, and it was cut by hand in record time. As far as is known, Marcus did eventually die as portrayed in the film.

I recommend this film to get a sense of what was going on in Israel immediately before and after the Declaration of Independence in 1948. Just keep in mind that it’s fictionalized history: if you are curious about particular details, then a little bit of research is required.

Crossing Delancey

Crossing Delancey Live and Become

Live and Become Biloxi Blues

Biloxi Blues The Jazz Singer

The Jazz Singer