Enemies, A Love Story (1989) is based on an Isaac Bashevis Singer novel of the same name. It tells the tale of four Holocaust survivors whose stories are intertwined by ties of passion, guilt, and love. Herman Broder (Ron Silver) was hidden in a barn in Poland by his Gentile house servant, Yadwiga (Margaret Sophie Stein) whom he married out of guilt and gratitude when the two immigrated to the United States. Since that time, he has acquired a mistress, a Russian Jewish survivor named Masha (Lena Olin), who wants him to marry her, too. Then his first wife, Tamara (Anjelica Huston) the woman he believed died in a concentration camp in Europe, turns up in New York too, alive if not well, still mourning their two children who did not survive.

Enemies, A Love Story (1989) is based on an Isaac Bashevis Singer novel of the same name. It tells the tale of four Holocaust survivors whose stories are intertwined by ties of passion, guilt, and love. Herman Broder (Ron Silver) was hidden in a barn in Poland by his Gentile house servant, Yadwiga (Margaret Sophie Stein) whom he married out of guilt and gratitude when the two immigrated to the United States. Since that time, he has acquired a mistress, a Russian Jewish survivor named Masha (Lena Olin), who wants him to marry her, too. Then his first wife, Tamara (Anjelica Huston) the woman he believed died in a concentration camp in Europe, turns up in New York too, alive if not well, still mourning their two children who did not survive.

The story is structured as a farce, but it is a dark and melancholic comedy. Herman writhes among the complications of his multiple lives. He is a man devoid of hope: he ricochets from woman to woman, trying to placate one while he is cheating on another. He is faithless, and at the same time, horrified by the faithlessness of others. He is a man who is never fully alive, living bits of his life with different women. Even his occupation – ghost writer for a fashionable rabbi – leaves him without any identity of his own. Herman is a ghost.

We often say, glibly, that after a trauma a person is “never the same.” Singer suggests to us that even after a horrible trauma, people do not really change all that much: they may be fractured versions of their old selves, but all of their old flaws and quirks remain like ghosts. Within a few minutes of meeting Herman again, Tamara (his first wife) recognizes that he married Yadwiga out of guilt and that he must also have a mistress somewhere. Later in the film, she sits him down and says, “In America, they have a thing called a manager. That is what you need. I will be your manager, because you are incapable of making your decisions for yourself.” He agrees – and in hindsight, the way that arrangement works out is predictable, too.

Paul Mazursky directed the film, and co-wrote the screenplay. (He also appearing in a cameo as Masha’s estranged husband. ) Enemies, A Love Story was nominated for three Academy Awards: Huston and Olin were both nominated for Best Supporting Actress and Roger L. Simon and Mazursky were nominated for Best Screenplay Based on Material from Another Medium.

Commentary

As with all of Singer’s stories, this is not a story about Judaism, but the characters are Jewish and it is set deep within Jewish history and tradition. At one point, when Herman is attempting to return to Jewish observance, he sits and studies Talmud on Shemini Atzeret and fumes, “What good is the Talmud if there is nothing in there to tell you how to deal with three wives?”

He apparently had not looked at Tractate Ketubot, which has quite a bit of material on how to conduct polygamous marriages. However, the Talmud assumes that one is doing so in good faith, which is Herman’s problem. Polygamy is described in Biblical narrative, although the only happy marriages mentioned in the Bible are monogamous. In the Middle Ages, about the year 1000, Rabbi Gershom of Germany issued a takkanah [decree] forbidding polygamous marriage among European Jews, and that decree has had the force of law ever since.

But the multiple marriages are not Herman’s core problem; they are only a symptom of the problem. Herman’s problem was correctly diagnosed by Tamara: he cannot make a decision for himself, and as a result he is incapable of keeping a commitment. His problem is faithlessness. Just as he dabbles and struggles through the film with his commitment to Jewish observance, confusing his Polish wife who eventually converts to Judaism, he dabbles and struggles with his commitments to the women in his life.

Yadwiga is involved in a process of commitment in the film: she becomes a Jew. The progression of her engagement with Judaism is delicately portrayed. Living with Norman for years, she has become fairly knowledgeable about household mitzvot [commandments]: she is appalled when he turns on an electric lamp on Shabbat. In her upset, she swears at him using the names of Christian saints! She struggles to learn the words of blessings. Yet we have the sense, by the end of the film, that this has been a successful process of commitment: she seems happy and relaxed as a Jewish mother.

By the end of the film, Herman has disappeared altogether; he remains only as handwriting on an envelope. All that are left are the two women, Tamara and Yadwiga, who have formed an alliance reminiscent of Naomi and Ruth. They are linked by a bond of love and commitment, and Yadwiga’s child soothes Tamara’s bitter soul.

Double Feature

Paul Mazursky also directed Next Stop Greenwich Village, about Jews in New York in a different era. The other Hollywood film adaptation of an I.B. Singer story is Barbra Streisand’s Yentl.

Questions

1. If Norman Broder came to you for advice before Tamara’s reappearance, how would you advise him? Stay in his loveless marriage to Yadwiga? Cut off the relationship with Masha? Or end the marriage to Yadwiga and marry Masha? What does he owe Yadwiga? What does he owe Masha?

2. If Norman Broder came to you for advice after Tamara’s reappearance, how would you advise him? What does he owe Tamara?

3. Norman and Yadwiga start out as an interfaith relationship. Yadwiga converts to Judaism. Tamara and other Jewish characters speak of Yadwiga as a shiksa [filth] early on in the film. At the end of the film, how would you describe Tamara and Yadwiga’s relationship? Can you imagine and describe the changes that must have taken place in Tamara’s perception of Yadwiga, and how those changes might have taken place?

Ushpizin

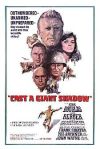

Ushpizin Cast a Giant Shadow

Cast a Giant Shadow