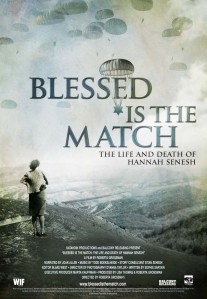

Blessed is the Match: The Life and Death of Hannah Senesh is an engaging portrait of a gifted young woman who sacrificed everything for her people. It’s hard to believe that this is the first documentary about her life. It’s almost harder to believe that Hollywood hasn’t made any kind of film about the life of Hannah Senesh, given its mixture of drama and pathos.

Blessed is the Match: The Life and Death of Hannah Senesh is an engaging portrait of a gifted young woman who sacrificed everything for her people. It’s hard to believe that this is the first documentary about her life. It’s almost harder to believe that Hollywood hasn’t made any kind of film about the life of Hannah Senesh, given its mixture of drama and pathos.

Senesh was a poet and diarist, a young Zionist who immigrated to Palestine in the 1930’s, only to return home to Hungary in 1944 as a Haganah volunteer to the British Royal Air Force. She and her small group parachuted into Europe, hoping to assist stranded British airmen and the Jews of Hungary. Their timing was terrible: days after they arrived at the Hungarian border, Germany occupied the country. Senesh was captured by Hungarian police and turned over to the Gestapo, who tortured and executed her in November of 1944.

In a twist that was certainly stranger than fiction, Hannah’s mother was imprisoned with her in Budapest for a time. The Gestapo was determined to force Hannah to give them radio codes that would allow them to send misinformation to the partisans and to the British. They arrested Mrs. Senesh and threatened to torture her to get her daughter to talk. Amazingly, Mrs. Senesh managed to survive the war (nearly all of Hungarian Jewry was murdered) and she appears in the film.

Synagogue-goers in the U.S. may be familiar with Senesh’s poem, Eli, Eli [My God, My God] set to a melody by David Zahavi.

Filmmaker Roberta Grossman waves together photographs, interviews, archival footage and dramatic reenactments to tell Hannah’s story. Scholars give just enough historical background for the viewer to understand exactly what this young woman was up against.

Commentary

The experience of Hungarian Jews was different from that of most of the Jews of Europe, in that as an ally to Germany, Hungary was not under the control of the Nazis until late in the war. Suddenly, in 1944, all of Hungary’s Jews were rounded up and sent to the death camps: in the space of a few months, most of the community was destroyed. Part of the power of this film is that it gives a very good picture of middle class Jewish Hungarian life before the war, as well as the darkest days of 1944.

It also conveys a particular kind of Zionist story, the story of a young Hungarian woman who immigrates to Palestine out of passion for the Jewish people and the Zionist project. Had she not become a parachutist, Senesh would likely be a retired farmer in Israel, telling stories about her life on Kibbutz Sdot Yam.

This film is gentle enough for middle-schoolers to watch, but retains an emotional punch. The mother-daughter relationship is presented with remarkably little sentimentality. I got the sense of two strong Jewish women who, under extreme pressure, found they were stronger than they knew.

This is an excellent film for learning about Zionism and about the Holocaust. Large events in history are much more comprehensible when we view them through the lens of a particular life. Hannah Senesh’s life is such a lens, and more.

Crossing Delancey

Crossing Delancey Kissing Jessica Stein

Kissing Jessica Stein Yentl

Yentl